While tobacco may not be a pleasant business to be in, not many people would dispute how lucrative it has been. Lorillard shareholders, in particular, will probably have been breaking out the bubbly recently as they digested the details of their company’s $27.4 billion acquisition by Reynolds American. However, I can’t help wondering how Lorillard’s former owners–the hotels to insurance conglomerate Loews–will be feeling about this.

Loews Corporation

Loews is a conglomerate that comprises a mixture of wholly-owned subsidiaries (high-end hotels and natural gas exploration and production) and controlling interests in several publicly traded companies (insurance, oil and gas drilling rigs, and gas pipelines). The company is similar to Berkshire Hathaway in that it started life as something very different to its present day purpose; in the case of Loews it used to be a chain of movie theatres before it was taken over by the formidable Larry Tisch, an ambitious and clever hotelier, who went on to build the company up to a diversified conglomerate. Today it is $17 billion dollar business run by two of his sons, and other family members.

The Tischs are known as deep value investors and are quite content to sit and watch the market, rather than invest in something without a large margin of safety: “We have asbestos-lined pockets”, is how Jim Tisch puts it. Others might say that they are more boring to follow than artificial grass. But being boring doesn’t seem to play well on Wall St. and, consequently, Loews seems to sell at a nearly permanent discount to its book value (currently about 0.9). I don’t think this bothers Jim Tisch though because he loves buying back stock (as his Father did before him) and the company’s publicly traded share count has reduced from 1.3 billion to a remarkable 387 million today. Pretty soon the Tischs will have bored everyone but themselves out of the stock.

Loews and Lorillard

Loews bought Lorillard in 1968 without spending a penny of its own cash. According to the King of Cash, a biography of Larry Tisch, Lorillard shareholders got a Loews $62 principal amount, 25-year subordinated debenture paying 6 7/8%, plus one-quarter of a warrant to buy a Loews common share for $110. Analysts estimated the value to Lorillard shareholders was about $450 million.

Lorillard was a big contributor to Loews coffers in the years that followed and, according to Revere Research (now FactSet), whose work was cited in a Forbes article in 2007, it provided Loews with 21.5% of its sales and a very substantial 33.2% of its income in 2006.

Lorillard was cheap at the time of its purchase by Loews and it was still a cheap stock at the time of the separation; according to this article on Seeking Alpha it was trading on a forward 2009 P/E of only 12.5 and, by March 2009 had a market value roughly equal to that of Campbell’s soup. Today Lorillard’s forward P/E is 15.6 and its market value is 22 billion, while that of Campbell’s Soup is only 14 billion.

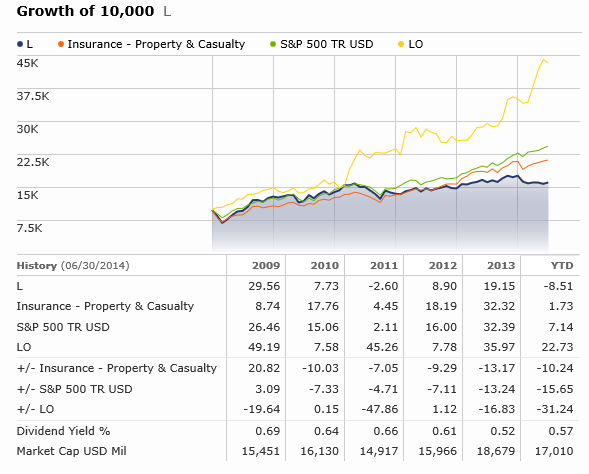

Value investing is supposed to be about buying low and selling high, not buying low and selling low which, unless I am missing something, is what Loews did here. The Morningstar chart comparing total returns for Loews (L) and Lorillard (LO) over the last five years reiterates the point:

According to the 2008 Loews annual report, net income included a tax-free, non-cash gain of $4.3 billion related to the final separation of Lorillard. As Loews shareholders were also entitled to swap their shares for Loews’ stake in Lorillard, Loews also managed to retire about 20% of its stock, which boosted its NAV and helped its share price (not visible in the above chart).

So why did Loews sell?

A look at the long-term returns of Loews immediately eliminates any doubt about their capital allocation skills, so why did they separate from Lorillard here?

Before the separation, Loews had acquired an increasingly complicated capital structure. In 2002, Loews had set up the Carolina Group, which was a tracking stock, to represent the interest in the economic returns of Lorillard and theoretically enable its value to be more easily recognised by the market. Several further blocks of shares had been sold in this over subsequent years and so Loews had already begun to put distance between itself and Lorillard. By fully spinning-off Lorillard, Loews could simplify its balance sheet and grant the CG shareholders full interest in Lorillard.

In addition, the separation would have made sense for Lorillard because it enabled its management to pursue options that may not have been possible under the conservative and ever prudent eye of Jim Tisch–that is, taking on debt, making acquisitions, not paying all earnings out as dividends and so on.

But I don’t think that simplifying the capital structure alone would have justified the separation; that sounds like nothing more than a pleasant side effect to me. Granting more freedom to Lorillard management sounds more plausible, but why would Loews want to give up all interest in Lorillard if they believed in, and wanted to empower, the management?

They certainly didn’t need the cash. Does Loews ever need cash?! Neither did they seem to have anything particularly pressing to use it for and so opportunity cost was not a factor.

I suspect that the reason they got rid of Lorillard just might have been because they were simply uncomfortable in the tobacco business. In a biography of Larry Tisch (the King of Cash), Billie Tisch (Larry’s wife and Jim’s Mother) is quoted as follows:

Would we buy such a company today? Absolutely not. But having it, there is a responsibility to the industry.

Even the pugnacious patriarch Larry Tisch seemed to harbour reservations:

Am I happy with what I did? I don’t know. I’ll never know. What am I going to do, go flog myself every day?

Loews’ ownership of Lorillard eventually necessitated Larry’s son, Andrew’s, appearance as part of the famous line-up of tobacco company executives before Congress in 1994 to justify why cigarettes shouldn’t be regulated as an addictive substance. This is one of the low points in US corporate history and history now records Andrew Tisch as having played his part:

According to the NY Times:

Mr. Waxman asked Andrew H. Tisch, the chairman and chief executive of the Lorillard Tobacco Company whether he knew that cigarettes caused cancer. “I do not believe that,” Mr. Tisch answered. “Do you understand how isolated you are from the scientific community in your belief?” Mr. Waxman asked. “I do, sir” Mr. Tisch said.

If I am right, and they did just want out of a business they did not like, then it is one in the eye for the legions of armchair cynics who believe that to be a capitalist (and especially a successful capitalist) is to be a ruthless, cold-blooded accumulator. That ain’t necessarily so. Once again, I will have to consider my own portfolio because I own no less than four different tobacco companies now including, via Reynolds, that former Loews cash cow Lorillard.

Disclosure: Long RAI [ahem].

Disclaimer: This post is not a recommendation to either buy or sell. Please consult your investment advisor.